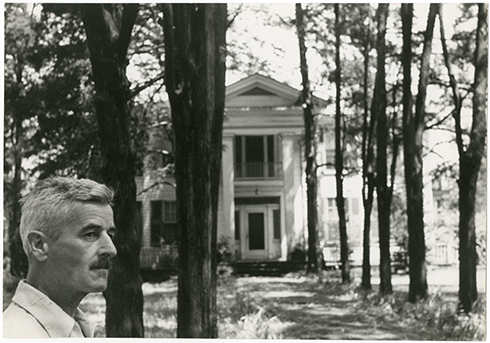

This year’s 39th annual Faulkner and Yoknapatawpha Conference marks the fiftieth year since William Faulkner’s somewhat sudden death in July 1962. This year the Conference organizers called for full panel proposals. Given that the conference theme is “Fifty Years after Faulkner” and will reflect upon, re-exaxmine, and reappraise his work within the past fifty years, a panel on Faulkner and the digital humanities seemed like the obvious, if not responsible thing to do.

I waited for a CFP to come up. None did. Never one to pass up an opportunity to fill a gap when I’m qualified, I came up with my own panel CFP.

Then I waited for wonderful abstracts to flood my mailbox. I got one abstract. Thank goodness, it was a really good one. But, needless to say, the drought of papers was disappointing.

The dearth of papers related to Faulkner and digital anything, however, might be broadly indicative of the current state of Faulkner studies. That is, not too many people are thinking about Faulkner in digital terms. Why? One reason is institutional support: Creating a major digital project requires lots of money and talent, both from the humanities and the computer sciences. But the bigger, and maybe sadder, reason is that the number of people committed to studying Faulkner’s life and work may be dwindling, particularly outside the South. Few American students get through grade school without reading “A Rose for Emily” and / or “Barn Burning,” short stories that make it into almost every short story anthology not because they’re necessarily the greatest short stories Faulkner ever wrote, but because they’re the few available to be anthologized. Advanced students might read As I Lay Dying or possibly The Sound and the Fury. And then they read (as they should) other things, graduate, get jobs, have a mid-life crisis, get over it, and die.

Some of those students might read other things and maybe, while reading, encounter writers with a dynamic digital component, whether an online archive, pedagogical and / or research tools. Maybe that digital project wants collaborators. And those resources and opportunities may be one reason why those students are drawn to, for example, the work of Walt Whitman and Willa Cather (or William Blake or Christina Rossetti). Maybe that student goes on to get a PhD in literature (not a crazy idea). When I look at the tremendous site dedicated to Whitman, or the two devoted to Cather, or the number of sites devoted to specific periods or areas in literature, I think: maybe my next research project or teaching assignment will incorporate some of these rich resources. To be sure, Faulkner has some strong and truly wonderful, deeply creative digital projects associated with him, including John Padgett’s terrific resource, William Faulkner on the Web, and Stephen Railton’s incredible Faulkner at Virginia, Absalom, Absalom! Electronic, Interactive Chronology, and his newly launched, work-in-progress Digital Yoknapatawpha, but they feel like isolated instances and not part of a larger body of online resources (including a library archives and databases) and a working community of researchers working to bring Faulkner to students, teachers, researchers, Faulkner fans, and everyone else.

Fifty years after his death, Faulkner remains an important American writer. The best way to honor his life and his work, and the work of the many who have done so much over the years to make sure we understand and develop his importance to literature, is to use the trove of digital resources to read, enjoy, and think anew about his work. My panel proposal, therefore, is an important one because it seeks to raise awareness about the need for bringing Faulkner more deeply into the digital world and to ensure his presence remains with us.

You must be logged in to post a comment.