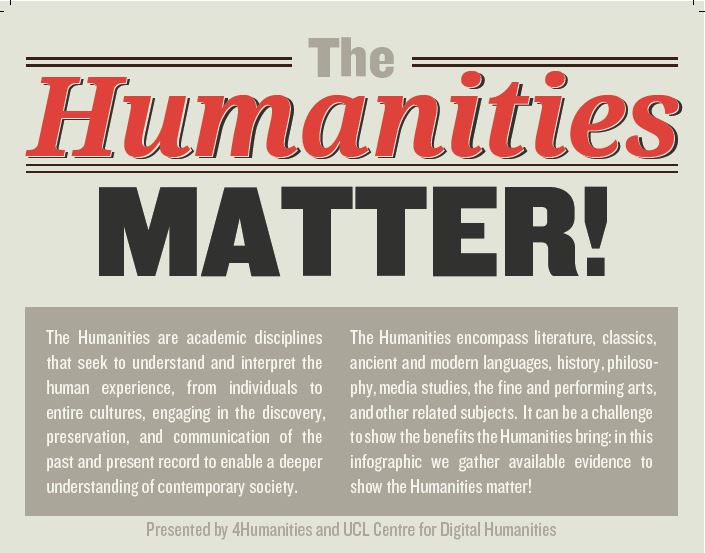

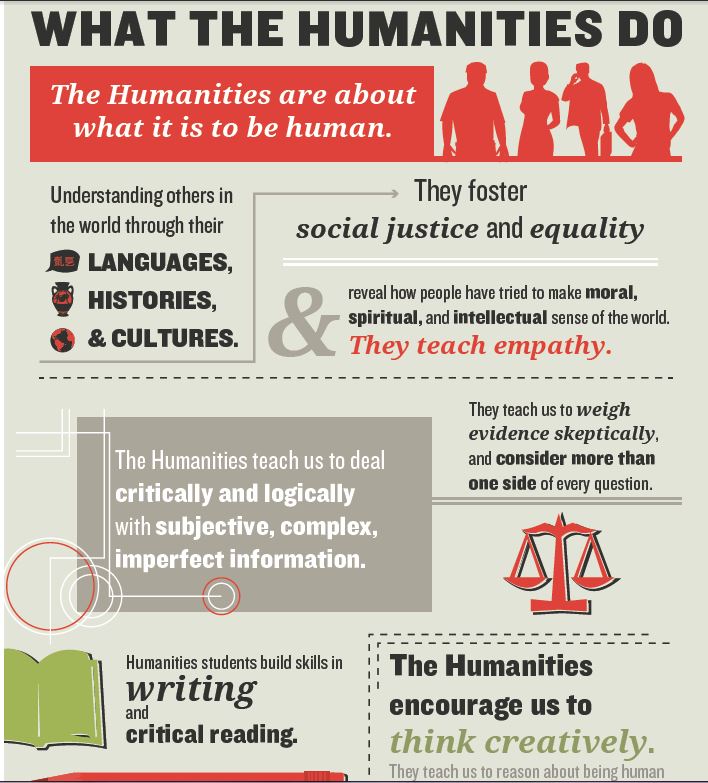

The good thing about all the doom and gloom over the so-called demise of the humanities is that it has caused humanities people to think about why the humanities are important and to quantify their place in our culture (see, for example, “Why English Majors are the Hot New Hires” by Andy Smith). One response to the “humanities is in crisis” debate comes in an infographic, The Humanities Matter!, from the University College London (UCL) Centre for Digital Humanities and 4Humanities.

The infographic visualizes statistics and arguments for the humanities, and some of the statistics might be surprising. For example, did you know that a “2012 survey of 652 US-born Chief Executive Officers and Heads of Product Engineering showed [that] almost 60% had degrees in the Humanities”? The entire banner, which has a Creative Commons license, can be downloaded here.

Imagine, for a moment, what it would be like if we did not have novels, poems, biographies, as well as film and television. All the things that examine and challenge our understanding of what it means be human. We might have poor imaginations, for one thing.

Without the humanities, I imagine it would be a little like living on Camazotz, the planet ruled by a big, bad brain called IT in Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. When Meg, Charles Wallace, and Calvin arrive on the planet for the first time, they encounter a neighborhood where all the houses look alike. That’s not so strange to them as is the sense that something is “off” about the children who are outside, skipping rope and bouncing balls. Charles Wallace figures out what’s wrong: “Look!” he says. “They’re skipping and bouncing in rhythm! Everyone’s doing it at exactly the same moment.”1 They quickly discover that people on Camazotz can’t think for themselves. They can’t make up stories or question anything. The humanities doesn’t exist on Camazotz. But when Charles Wallace gets trapped by IT, it is Meg’s stubbornness and her deep love for her brother that helps him escape. She realizes that these two things, which are integral to her humanness, are potent weapons against IT’s mind control.

Without the humanities, Albert Einstein might only have studied science and math. Imagine if he’d ended up in that patent office in Bern, Switzerland until he died, spending his whole life testing out other people’s inventions. Imagine if Einstein hadn’t been acquainted with the philosophy of Spinoza, which helped shape his understanding of order and determinism. How might that have altered his formulation of the theory of relativity? If Einstein had never learned to play the violin, how might that have affected his ability to arrive at E=mc2? How would he have relaxed his big, amazing brain? We don’t know these answers, of course. But, as humanists, we can speculate and imagine, “what if.” In fact, that’s what Einstein did. He asked, “What if the ether did not exist?” If he hadn’t asked that question, if he had assumed like everyone else that the ether existed, he might never have discovered the theory of relativity. The scientist and the humanist have many things in common.

1 L’Engle, Madeleine. A Wrinkle in Time. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1962. Pg. 103.

You must be logged in to post a comment.